Did you know that the rectum has a totally different pH than the vagina? That depending on how you like to have sex, you may need more than one bottle of lube handy? That the wrong ingredients in a personal lube can actually dry out your tissues more than hydrate them? Did you know that glycerin is a sugar…sort of…but that’s probably not why that cheap bottle of lube gave you a yeast infection?

I spent the first half of 2024 researching and writing The Best Personal Lubricants for Wirecutter. Go check it out if you haven’t yet!

As always, what actually makes into the final Wirecutter guide is a mere sliver of of the research I conduct to make the final picks. I interviewed several OB/Gyns, a urologist, two cosmetic chemists, representatives from different lubricant companies, sex educators and sex toy retailers as part of the process of selecting the six “best” lubes. The quotation marks are there because all of the lubes we tested were very good, and what might be the best lube according to our testing criteria might not actually be the best lube for you! If there’s anything I learned from this process, it’s that everyone has their favorites, and will defend them with vehemence.

Your average Wirecutter reader is looking for a straight forward recommendation, and is probably not interested in reading all my nerdy research notes. But if you’re here, you probably do. If you’ve read this far, it means you’re a sex nerd, and you love the ins and outs (pun intended) of sexual health research! Welcome, fellow nerd!

I mistakenly thought that researching this guide would be a fairly simple endeavor. After over a decade in the sex educator game, I thought I knew all there was to know! (If if you don’t know the basics, please do read the guide.) I knew that there was water, silicone, and oil based lubes. I knew that you shouldn’t mix silicone toys with silicone lube, you shouldn’t mix oil based lube with condoms, and I *thought* that glycerin and propylene glycol were bad ingredients (more on this later).

I had no clue how deep the rabbit hole went with this. Those six months of research were deeply humbling to what I *thought* I knew. Allow me to share eight things I learned about lube as a veteran sex educator writing the Wirecutter Lube Guide:

1. Nobody can agree on anything.

Fuck it, I’m just going to lead with this. This will make more sense as the article progresses, but let’s just say that the reason there’s so much misinformation about lube is because the MDs, sex educators, retailers, cosmetic chemists and brand reps I spoke with CANNOT AGREE ON ANYTHING.

Even consumers cannot agree with themselves. I was told an anecdote about an individual who reported chronic vaginal infections with one particular brand of lube, but swore by another brand which was apparently the same formula being sold under a different brand name. More on that later, too.

2. pH matters with water based lubes, and you might need different water based lubes for vaginal and anal use.

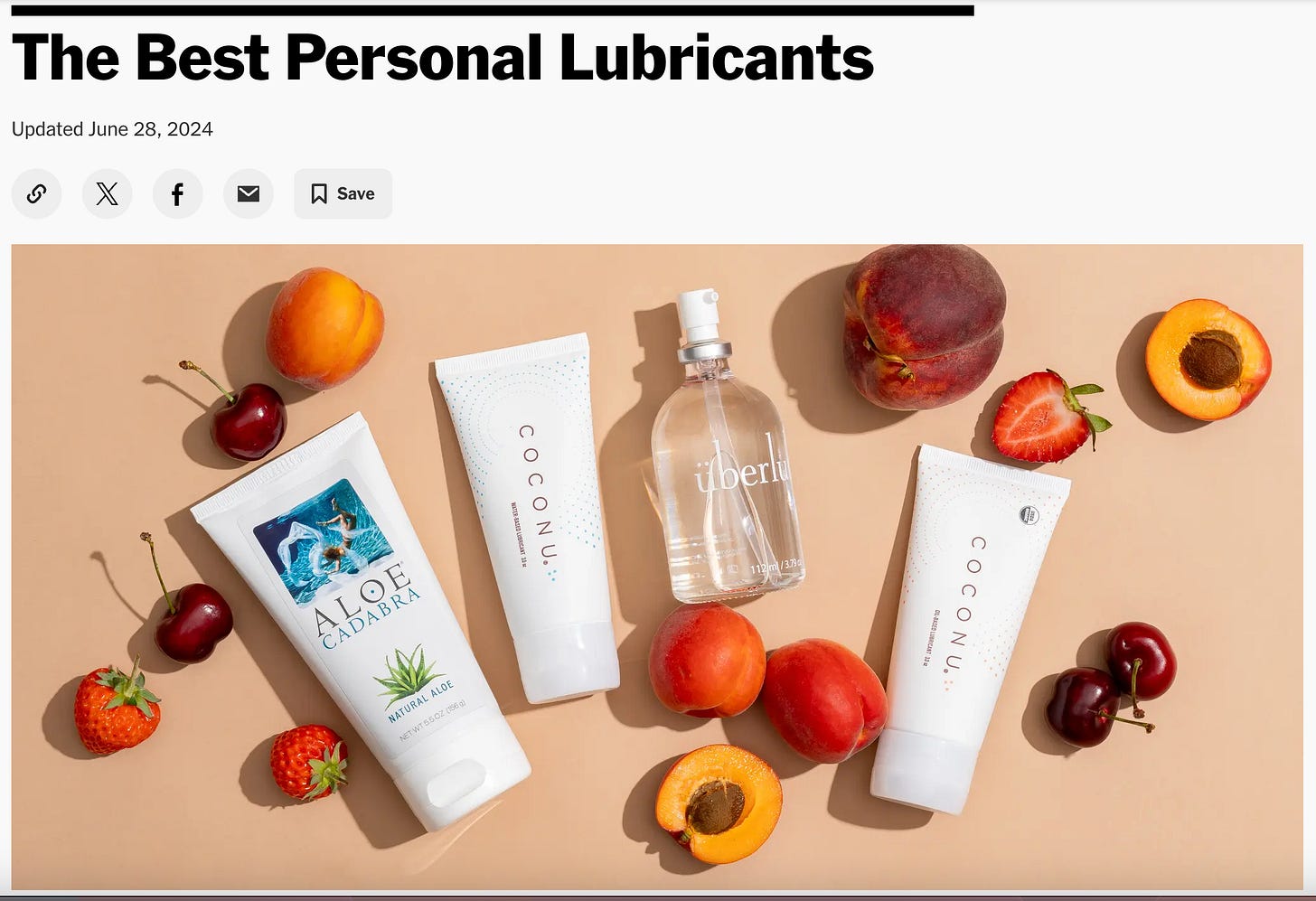

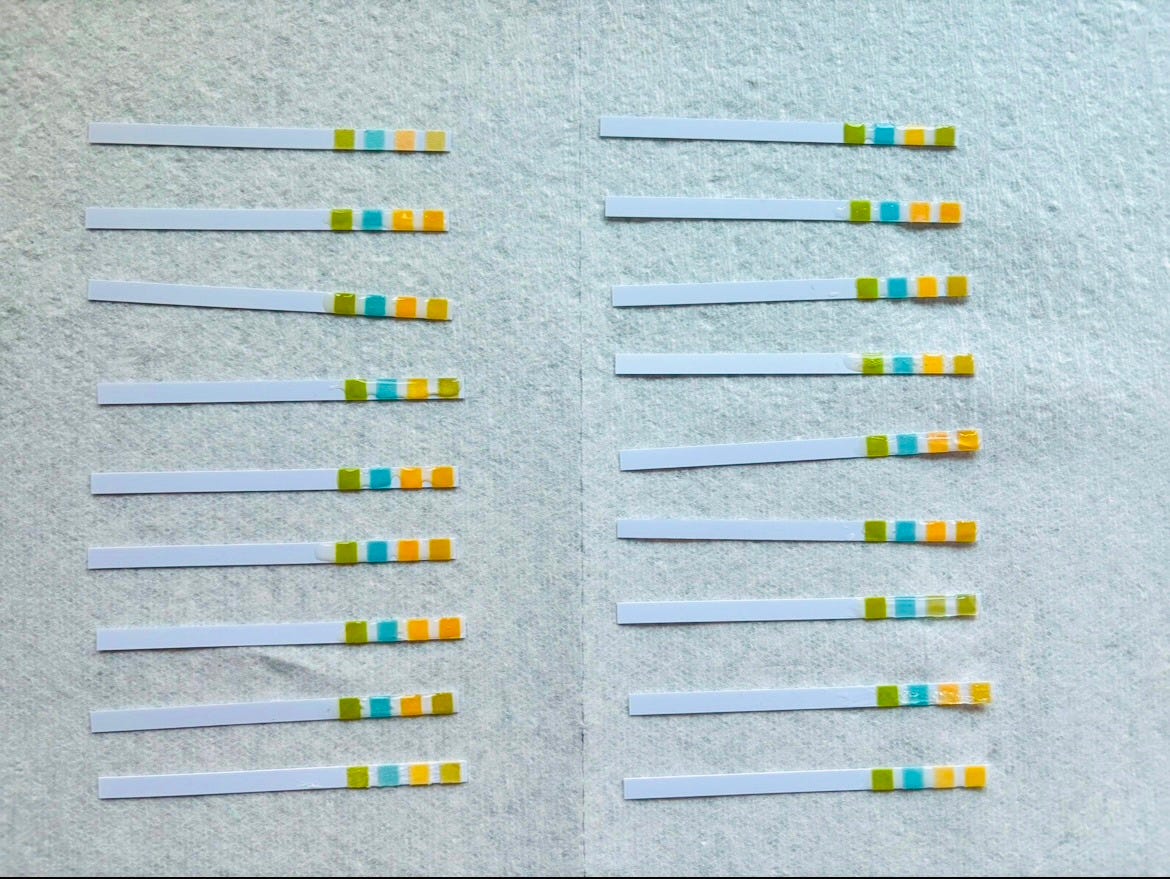

pH describes the “quantitative measure of the acidity or basicity of aqueous or other liquid solutions.” The pH scale ranges from 0 to 14. Everything below a neutral 7 (pure water) is acidic (vinegar is 2-3), while everything above 7 is basic (baking soda is 8-9). Pure water is a 7, vinegar is 2-3, baking soda is 8-9. You may have seen pH testing strips in laboratory or clinical settings, you can actually buy these online and test various water-based liquids for fun if you’re that kind of nerd. (I am!)

I bet you didn’t know that the pH of the water-based lube you use matters a lot. It does!

A healthy pH for a vagina between adolescence and menopause is about 3.8-5. During and after menopause, natural vaginal pH becomes more basic, in the range of 5-7.5 (please note that HRT usage will lower these numbers).

A healthy pH for a human rectum is more neutral or basic, in the range of 7-8.

Most water-based lubes that advertise themselves as “pH balanced” clock in the 4-6 range, to be friendly to the vaginal biome. This level of acidity is great for keeping vaginal infections at bay, but can be too acidic and irritating if you are using the same lubricant for anal play.

I’ve always been somewhat averse to using water based lubricant for anal activities because of the spicy “burning” sensation I encountered with many brands. I never got this burning when I used silicone or oil based lubes. I always assumed it was because I had sensitive skin and was allergic to something in water based lube, but now I understand that I was using lubes that were too acidic! The bad news is even some water based lubes that claim to be “backdoor friendly” are not actually pH balanced for anal use.

Does this mean you should have separate bottles of water based lubricant for vaginal and anal play (if you regularly enjoy both)? Very likely yes! Both delicate anal and post-menopausal vaginal tissues benefit from using a thicker, more cushiony lube, and many of these higher pH formulas are also thicker.

Some of the water-based lubes we looked at that are higher pH and thus ideal for these applications include Sutil Rich (5-6), Slippery Stuff Gel (7), Exsens Pure Aqua (5-6), Wicked Simply Timeless Aqua (5-6), and Boy Butter H20 (5-6, my personal fave for anal play, but should not be used vaginally). These are my approximate pH values based on measuring these lubricants with an at-home pH testing kit for the lube guide.

What about silicone and oil based lubes? These are anhydrous formulas (chemistry speak for “does not contain water”) and thus are pH neutral. Hybrid silicone/water lubes such as Sliquid Silk do contain water and have a pH, however.

3. Osmolality matters. Or does it?

Osmolality is another fancy chemistry term. According to Healthline:

Osmolality is a measure of how much one substance has dissolved in another substance. The greater the concentration of the substance dissolved, the higher the osmolality. Very salty water has higher osmolality than water with just a hint of salt.

So what does that mean when it comes to lube and your body? When it comes to the osmolality of a personal lubricant, it can determine how much fluid is either added to, or drawn out of the cells of your vaginal or anal mucosa in order to achieve and maintain equilibrium and homeostasis. If a lubricant has a much significantly higher osmolality than your mucosa, it will draw water out of your tissues, potentially causing damage.

(Once again, we are talking about lubes that contain water. This is not a factor for anhydrous oil and silicone based lubricants.)

The vagina has an osmolality value of about 260-290 mOsm/kg, with the colon in a similar range of ∼290 mOsm/kg. According to a report from the World Health Organization:

Ideally, the osmolality of a personal lubricant should not exceed 380 mOsm/Kg to minimize any risk of epithelial damage. Given that most commercial lubricants significantly exceed this value, imposing such a limit at this time could severely limit the options for sourcing personal lubricants for sector procurement. It is therefore recommended on an interim basis that procurement agencies should source lubricants with osmolalities of not greater than 1200 mOm/kg.

So basically, it is preferable to choose a lube with an osmolality similar to your vagina/rectum, ideally under 1200 mOm/kg.

Unlike pH levels, osmolality testing is not something you can do at home. Some companies will list their osmolality values in their marketing materials, but some smaller boutique brands may not conduct osmolality testing at all, as it can be complicated and expensive to perform.

According to WHO’s research, osmolality seems to be correlated with high levels of glycols and glycerols in a lubricant’s formula. Glycols and glycerols are organic compounds in the alcohol family, and they most frequently show up in lubricants in the form of ingredients such as propylene glycol (PG), propanediol (PDO), and glycerin. There has been a lot of misinformation about these lubricant additives in sex education communities, and I will do my best to set the record straight in the next section.

As it relates to osmolality, WHO recommends that lubricants should not contain more than 8-9% of these compounds in a formula, so look at the ingredient label. If propylene glycol is towards the end of the ingredient list, it’s probably fine; you may want to avoid the product if it’s the first ingredient listed. Conversely, don’t chuck the bottle if it’s the second ingredient; it’s possible that the lube is 95% water with 3% PG.

Of course, no sooner did I learn how to pronounce “osmolality” that I encountered naysayers who argue that osmolality is not a perfect metric for assessing a good quality lube.

Bruce Albert, chief scientific officer at CC Wellness, (makers of the System Jo and Lube Life lines), told me that their company aims to stay within the WHO recommended range rather than citing a specific number, because osmolality testing is not a perfect science:

“We get a lot of variability in osmolality when we do our testing. You can send a sample in today and get a certain number and and the same sample a week later and get a completely different number. For us, as long as we fall within The World Health Organization’s guidelines, and we are well within that with all of our lubes, that's how we operate.”

(Excerpt from phone interview conducted 3/29/24).

Hathor/Sutil, the makers of Sutil Rich, which the Wirecutter guide recommends as a thicker water-based lube, took the hardest line against osmolality of any company I spoke with during my research process, and stated the following:

“We have stopped talking about Osmolality because after spending over two years researching, reformulating and working with different labs we and others have come to the conclusion that the research on Osmolality is controversial and inconclusive. Too little information can be dangerous and misleading.

One interesting detail that came up is the fact that some high Osmolality lubes show cellular irritation while others with the same or higher Osmolality do not.

The high Osmolality Lubes that caused cellular damage also contained similar toxic chemicals and parabens that should more importantly not be found in your lube.

Another point that came up is that low Osmolality lubes do not last. They dry up quickly and in themselves cause irritation and abrasion.”

(Excerpt from “Conclusions on osmolality” a PDF received from the Hathor/Sutil team on 4/16/24).

I present their perspective for consideration without necessarily endorsing it. (It has not been my personal experience that low osmality lubes don’t last.)

So, back to point #1: nobody can agree on anything.

4. Glycols and Glycerols are not universally evil.

Is propylene glycol really just a fancy name for antifreeze, and is using a glycerin-based lube the same as dumping sugar in your vagina? (This is the title of a forthcoming Lana Del Rey album, BTW).

As promised in the previous section, let’s dig into what glycols and glycerols actually are, and whether or not you need to be scared of them. (Disclaimer: I am not a chemist). To refresh your memory:

Glycols and glycerols are organic compounds in the alcohol family, and they most frequently show up in lubricants in the form of ingredients such as propylene glycol, propanediol, and glycerin.

Glycols and glycerols are used in industrial manufacturing, cosmetics, skincare, and yes, even food. While PG’s cousin ethylene glycol (EG) is super toxic and used as an industrial antifreeze, I promise you EG is never going to show up in your personal lubricant. Unlike EG, ones I mention above are all generally regarded as safe (GRAS) by the FDA.

These compounds serve a lot of different purposes in consumer products, acting as a solvents, preservatives, thickens, emulsifiers, humectants (high osmolality draws moisture into the product from the ambient environment). They also can be used to lower the freezing point of a product, hence the antifreeze panic. I hate to break it to you, but it’s often added to ice cream for the same reason. Glycols and glycerols are commonly added to personal lubricant formulas to give the product the viscous and slippery feeling that water alone cannot provide.

Propylene Glycol is FDA approved for use in food and cosmetic products. Both of the cosmetic chemists I interviewed for the guide think that consumers are unnecessarily concerned about the threat that PG poses within lubricants. While a very small percentage of people are allergic to PG, you’re probably already eating propylene glycol and rubbing it into your skin without realizing it; it’s often contained in the catch-all of “natural flavorings” in food products. It’s the first ingredient in those flavored Bubly drops you add to sparkling water.

“According to the World Health Organization, the acceptable dietary intake of propylene glycol is 25 mg of propylene glycol for every kilogram (kg) of body weight.” For a 150 pound person, that’s 1700 mg of propylene glycol. According to my imperfect math (Google AI) “a single serving of Bubly Drops (around 3/4 teaspoon) contains approximately 100 mg of propylene glycol.” If we consider 3/4 tsp (3.7 ml) to be a serving, that’s 17 servings of Bubly drops, and a 40 ml bottle of Bubly Drops contains about 11 servings (Bubly Drops’ consumer label considers a single serving to be 1/4 teaspoon but most people realistically use more). This means you could hypothetically chug 1.5 bottles of uncut Bubly Drops in a sitting and be okay.

My apologies for singling out Bubly for this thought experiment. While I am not a big fan of the drops, Bubly Cherry in the can is my favorite seltzer and I probably drink it in excess of legally recommended limits. (They did not pay me to say this.)

Where were we?

Okay, so backpedaling a little: a small amount propylene glycol is not going to kill you, and is not the same as dumping commercial antifreeze on your genitals.

As it relates to osmolality, WHO recommends that lubricants should not contain more than 8-9% of these compounds in a formula, so look at the ingredient label. If propylene glycol is towards the end of the ingredient list, it’s probably fine; you may want to avoid the product if it’s the first ingredient listed. Conversely, don’t chuck the bottle if it’s the second ingredient; it’s possible that the lube is 95% water with 3% PG.

It’s worth noting that many lube companies have switched from using Propylene Glycol to Propanediol due to consumer concerns. PDO has the same chemical formula as PG but a different chemical structure, and behaves in similar ways. It has the benefit of being usually derived from corn rather than petrochemicals, making it more eco-friendly, and there are reports that it is less likely to trigger skin irritation than PG.

Let’s talk about Glycol’s O-chem cousin Glycerol, notably glycerin. Glycerin is used in food, lubricants, and other skin care products for many of the same reasons as PG and PD. You may have heard that glycerin is a sugar, which is why some people blame glycerin containing lubricants for triggering vaginal infections.

Glycerin does indeed taste sweet, its name comes from the Greek word glukús, meaning sweet. However, it is a sugar alcohol, a compound that is quite chemically different from table sugar (sucrose). Like PG, it is GRAS by the FDA, and is used a food additive, as well as a humectant (moisturizer) in many skincare products. You may have seen sugar-free confections sweetened with other sugar alcohols such as erithrytol, maltitol, xylitol marketed as low carb diet foods. While some folks anecdotally swear that glycerin triggers a yeast infection in their bodies, the chemists I interviewed do not believe that sugar alcohols are a ready source of food for yeast. Conversely, medical-grade Glycerin is sometimes used in wound dressings due to its anti fungal and anti bacterial properties. Therein lies the rub. A good quality glycerin-containing lube SHOULD use vegan, medical grade glycerin, and not all of them do. Rebecca Pinette-Dorin of the french lube brand ExSens (which makes a low-osmolality glycerin based lubricant) does an excellent job of explaining and debunking glycerin as a boogeyman ingredient in this blog post.

In some cases the culprit may not be glycerin itself, but a too-high osmolality or pH which caused the vaginal biome imbalance. It’s important to remember that there are a lot of reasons why some people are prone to vaginal infections including stress, hygiene, hormones, and so forth.

That said: if you find that a particular brand of lube triggers an imbalance EVERY time you use it, stop using it, and find one that doesn’t trigger an infection! There are any number of reasons why your body many not agree with a particular type of lube, and at the end of the day you should use what works for you.

5. Personal lubricants are classified as Type 2 medical devices by the FDA, and are supposed to have FDA approval, but it’s not really strictly enforced.

The topic of FDA approval was an unexpected hurdle that came up in writing the lube guide. Not to quote myself or anything:

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies lube as a Class II medical device, the same class as menstrual cups and tampons. However, the agency considers menstrual cups exempt, meaning their manufacturers need not apply for premarketing clearance. Lube makers, on the other hand, are supposed to apply for FDA 510(k) clearance and demonstrate their products’ safety and efficacy. Some lube makers advertise their products as intimate moisturizers or massage oils rather than personal lubricants; in the absence of specific claims “to treat or prevent disease or otherwise affect the structure or functions of the human body,” these may be considered cosmetics—and therefore, not beholden to the FDA’s clearance requirement.

The FDA clearance requirement for personal lubricants is a relatively new thing (as of 2011 according to one of the cosmetic chemists I interviewed, though I can’t seem to find confirmation of this timeline anywhere else), and not strictly enforced. While FDA approval of a product that you liberally apply to your mucus membranes might seems like a no brainer, there are some very good reasons why smaller, cruelty free companies might not want to pursue 510(k) clearance. It’s expensive, time consuming, and requires animal testing (CW for that ahead). According to this article in Vice:

John Goepfert, CEO of the lube maker Simply Slick, says the process to get 510(k) for his company took about two years and cost over $200,000.

And:

Lab workers also spent five days injecting the lube into the vaginas of New Zealand white rabbits in order to check for possible discharge, irritation, and infection.

Yikes.

FDA clearance was one of the factors I looked at when writing the lube guide, but it wasn’t an absolute deal breaker, nor was it considered to be by the majority of Doctors I interviewed. Two of the lubes we recommended (Sliquid Silk and Sutil Rich) do not have FDA 510(k) clearance, and a third (Coconu Oil Based) was in the process of obtaining approval.

6. Private label lubes are a thing.

This is something I learned about as a “hush hush” industry secret at a trade show, but just like how Costco Kirkland Vodka tastes suspiciously like another brand of French vodka, I was told by credible sources that the same lubricant is sometimes sold under multiple brand names. While I don’t consider this to be a make or break factor when shopping for lube, you will know for sure that a company is selling a proprietary product if they have an in-house chemist, and are able to tell you about the product’s pH, osmolality testing, and FDA clearance or lack thereof.

7. Price matters, but only to a point.

Buying lube is sort of like shopping for a decent bottle of wine: you don’t necessarily want the cheapest product on the market, but beyond a certain price point you’re mostly paying for hype.

The lubes we recommended in the Wirecutter guide ranged in price from about $3 to $9 per ounce, which means an average-sized bottle of good quality lube will typically run you between $10-$30. Our water based fave Aloe Cadabra is a very reasonable $10-$12 (depending on retailer) for a 2.5 ounce bottle. The most expensive lube we tested for our guide was $24/oz, and while it was very good, it wasn’t better than the ones we tested that were a fraction of that price.

There are exceptions to every rule, and there are a handful of good quality inexpensive lubes that I recommend, including Lube Life (about $1.24/oz) and Slippery Stuff (about $1.36/oz).

8. Some lubes may contain “Forever Chemicals.” Yikes.

This research about forever chemicals in condoms and lubes emerged around the time the lube guide went to print, so it didn’t come into play when we were making our picks. (Which is why of our picks is on their dirty list. Ack.)

I haven’t delved into the research deeply enough yet to present an informed opinion about actual potential risks of using the lubes they found to contain fluorines, but I wanted to present this information for your consideration. I will update both this article and the lubricant guide in future once I am better informed on this topic.

9. There’s no goldilocks lube that is perfect for everything and everyone.

Now we come full circle back to point #1: Nobody can agree on anything. Maybe we don’t need to?

Pick a lube that’s in your budget, that suits your needs. Maybe you’ll have to try a few different brands before you find your soulmate lube. Maybe you need a few different types of lube for different uses. I personally have different preferences for lube based on solo and partner play, what types of toys and barriers I am using, etc. One person’s favorite lube maybe give another person a horrible yeast infection. You know what? It’s okay. Not everyone has to love the same products. Normalize owning multiple bottles of lube!

Most importantly, use it. Please. Early and often. In abundance! ESPECIALLY if you’re putting anything in your butt.

XOXO

Bianca

Disclosure: I received the lubes I discuss in this post for free when I was working on the Wirecutter guide. I did not receive any compensation from any of these companies to include their products in this post, and have not included any affiliate links in the interest of journalistic neutrality specifically for the products I review for Wirecutter.

If you want to encourage me to continue doing this type of in depth science driven sexual health research, I encourage you to subscribe to my publication (both free and pledged helps), comment, restack, and if you wish to tip me for my work, you can find me on both Venmo and Cashapp as $VenusStarfruit.